Diversifying the medical profession for 30 years, looking ahead for more opportunities

Thesla Anderson’s family moved from the Bronx, New York, to the Virgin Islands when she was a child, hoping the climate would help doctors there heal her chronic breathing problems. Her successful treatment showed her what physicians can do and inspired her to become one herself.

Once in college, she excelled in her biology classes and her path seemed set – until she ran into organic chemistry and physics in her third year of studies. Ill-prepared and lacking a support network to help overcome the challenge, she realized she would not fulfill her dream of becoming a doctor. Changing her major, Anderson became a middle school science teacher. As a person of faith, she knew she was destined to help others somehow.

Through destiny, perseverance, divine intervention or some combination, Thesla Anderson ultimately fulfilled her goal of helping the medically underserved in a manner she never could have envisioned – and for which hundreds of physicians and other health-care professionals are profoundly grateful.

Last weekend, many of them joined Anderson and the Florida State University College of Medicine leadership team – including Interim Dean Alma Littles, M.D., and Senior Associate Dean of Interdisciplinary Medical Sciences Anthony Speights, M.D. – to celebrate 30 years of SSTRIDE, Science Students Together Reaching Instructional Diversity and Excellence. One of several FSU outreach programs Anderson had a hand in creating, SSTRIDE’s purpose is to help students from underserved populations overcome the kind of obstacles that derailed her plans to become a physician.

The SSTRIDE Alumni Leadership Conference in Orlando attracted alumni from throughout the country. They came to share their knowledge and expertise through continuing education seminars; form mentoring relationships with current medical students and undergraduate pre-medical students currently in SSTRIDE; pledge to help solidify SSTRIDE’s foundation to ensure the program will continue; and reconnect with old friends they met through the program.

The conference’s theme, “Expanding Health Care through an Interdisciplinary Approach,” included sessions and panel discussions emphasizing the importance of nutrition, exercise, preventive medicine including healthy lifestyle choices, and how artificial intelligence can help expand health-care access. Several were geared toward practitioner self-care, such as avoiding burnout and letting go of perfectionism. Many of the sessions focused on inter-professional collaboration to improve the lives of patients and their families, including a session on breaking barriers and creating a more holistic approach to mental health treatment and another on the lingering effects and lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The conference atmosphere was more of a joyous family reunion than a buttoned-down professional development workshop, which was no accident.

“The first thing we had to do when we created SSTRIDE was make the students realize they were part of a family that was here for them,” said Anderson, SSTRIDE's founder and now executive director of undergraduate outreach and pre-college programs for the College of Medicine. “‘Imposter syndrome’ is so common and so damaging, especially if you aspire to be something greater than where you come from.”

“Imposter syndrome,” defined as feeling anxious and not experiencing success internally, despite being high performing in external ways that can be measured objectively, often results in people feeling fraudulent or phony and doubting their abilities. Lacking a support network, students sometimes give in to those doubts and give up on their dreams.

“Once they embrace their new family and their own potential,” Anderson said, “they can let ‘imposter syndrome’ go and open themselves to the tutoring, coaching and directed self-study that will add to their knowledge base and bring them up to par with their peers.”

Throughout the weekend, attendees shared stories of how SSTRIDE changed their lives, and how they are committed to doing the same thing for future generations.

How SSTRIDE works

SSTRIDE started out working with educators in middle and high schools to identify students with an aptitude for or an interest in science, technology, engineering or math (STEM) fields. Participating schools created an elective course in anatomy and students either were identified as having potential to be health-care providers or self-selected to sign up and find out more about the medical field. After-school activities and advising on many educational aspects – including which courses to take to prepare for college, how to write an application letter, and how to gain more knowledge while accruing volunteer hours – remain a part of the program.

The program has grown from a single anatomy class to an introduction to health sciences class for middle school students, a biology class for ninth-graders, a chemistry class for 10th-grade students, an anatomy class for 11th-graders and a certification course for high school seniors. Students gain clinical experience as they become certified as emergency medical responders or nursing assistants. Students in the Immokalee program also have the option to become licensed practical nurses.

Undergraduate SSTRIDE (USSTRIDE) at Florida State continues to support students at FSU and Florida A&M University. USSTRIDE students tutor and mentor the younger participants, while receiving that “family” support and access to academic assistance if they need it.

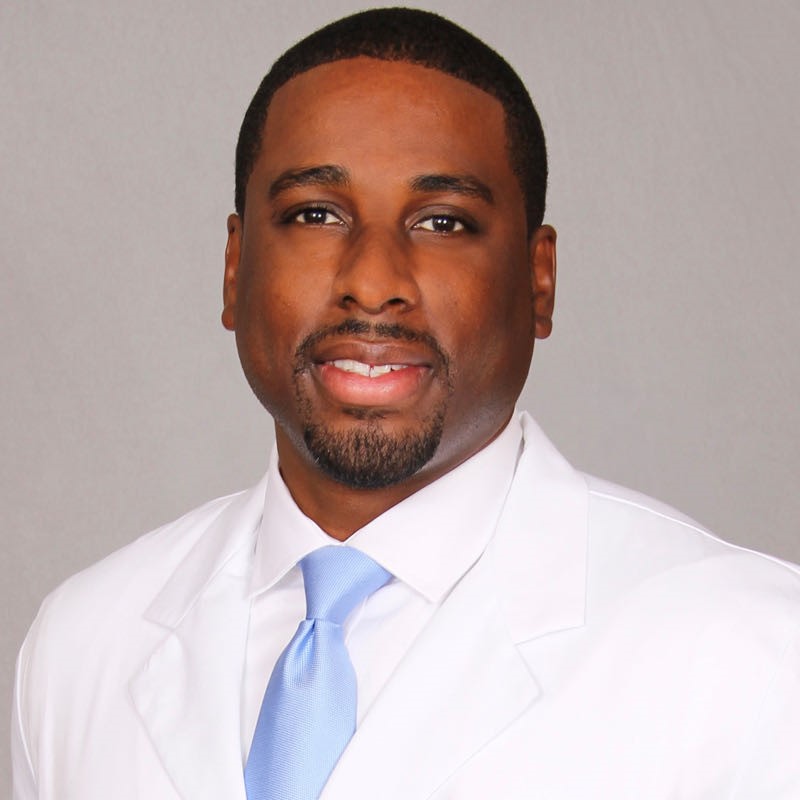

Many of the SSTRIDE alumni refer to Anderson as a mother figure, including Rashad Sullivan, M.D., an orthopedic surgeon who met his wife of 13 years, Natalie Alphonse Sullivan, M.D., a radiation oncologist, through USSTRIDE.

While a FAMU undergraduate student hoping for a career in medicine, Rashad Sullivan started out driving a van to pick up younger SSTRIDE students for after-school activities. He became a mentor, an instructor in an eighth-grade anatomy class and eventually became assistant coordinator of the program and evening supervisor for the Outreach and Academic Advising Department. He did any job Anderson asked him to do.

“I can’t say ‘no’ to her,” he said. “She did so much for me. I wouldn’t have my beautiful wife, our beautiful children or our beautiful life if it weren’t for her.”

As an FSU undergraduate student, Natalie was involved in the Minority Association of Pre-Medical Students (MAPS). She left Tallahassee for medical school at Wake Forest University the same year Rashad was accepted into FSU’s Bridge to Clinical Medicine program, where he earned a master’s degree in clinical sciences and acceptance into FSU medical school. They completed residency programs at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, N.C. Rashad also completed a fellowship in Adult Total Joint Reconstruction at Florida Orthopedic Institute in Tampa, and Natalie also serves as a clinical assistant professor at the Sarasota Regional Campus.

In his welcoming keynote breakfast address on Friday, Rashad Sullivan recognized Anderson as one of three “mother figures” he had at FSU. Another was Elizabeth “Liz” Foster, Ph.D., now associate dean of the interdisciplinary medical sciences (IMS) undergraduate program that is housed in the College of Medicine but administered by seven colleges throughout the university. Although he was a FAMU student, Rashad found Foster’s door was always open to him, he said. Foster was one of the presenters at the conference.

His third FSU “mother” was Myra Hurt, Ph.D., whose tenacious advocacy led to the creation of the College of Medicine and who is widely considered its godmother. Hurt, who served as interim dean until the first medical dean was hired, died earlier this year.

“She was such an extraordinary woman,” he said. “I was told the night I was accepted into the Bridge program, she was in the room, pounding her fist on the table with tears in her eyes, saying ‘If we’re not here for him, who in the hell are we here for?’

“It’s a shame she didn’t live to see this weekend,” Sullivan said, “because this, too, is her legacy.”

When the stars align

FSU’s College of Medicine was created by the Florida Legislature in 2000 explicitly to train physicians to serve the underserved in Florida, particularly minority, rural and elderly populations. Research has shown the best way to achieve that goal is to recruit students from those populations, who often lack the educational, financial, and emotional resources available to more affluent applicants. Thus, those students often do not score as well on the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) that aspiring medical students must take and is a primary consideration in medical school admissions. Hurt wanted to level the playing field.

In 1993, seven years before the Florida Legislature approved FSU’s medical school, Anderson applied for a job advising students in the Program in Medical Sciences (PIMS). In place for 20 years. PIMS primarily served FSU, Florida A&M and University of West Florida students who aspired to be physicians. By successfully completing their first year of medical school through PIMS, they were automatically admitted to the University of Florida College of Medicine for their final three years.

Hurt, named PIMS director in 1992, hired Anderson but assigned her a different mission: to create a program to bridge the gap in the number of women, minorities, and people from rural areas who applied, were accepted and successfully completed the PIMS program. After visits to Xavier University and Wayne State University, which had success in that area, Anderson created SSTRIDE with Hurt's blessing.

Helen Livingston, Ph.D., joined the team in 1996 and led the creation of the Bridge to Clinical Medicine program, after Hurt dropped a brochure about a similar program on her desk, saying, “We want one of these.”

At a virtual reunion of SSTRIDE alumni two years ago, Livingston explained that she developed the Bridge program, with Anderson’s assistance, for students who showed potential but were not quite ready for medical school. With more preparation, however, they could get ready in a year’s time. She ultimately molded it into the master’s in clinical sciences graduate degree program.

Messages of love and gratitude

Livingston, now retired, was one of the honored guests at the conference’s Saturday night 30th anniversary banquet, where testimonials from SSTRIDE alumni kept Anderson in tears. Alexis Kendall, a second-year medical student at the FSU College of Medicine, said Anderson was always there with love and support but always “kept it real” with honest critique.

"Once I did as she said, and I did exactly as she said, I was accepted into the Bridge program," Kendall said, adding that Anderson "didn't make just one doctor, she made many doctors."

Minutes later, Dr. Bernard Ashby told Kendall from the podium that Anderson delivered similar honest critique to him.

“She told me, ‘You’ve got to step your game up,’” he said.

"I was motivated, but I did not have the tools for success -- at all," Ashby told the crowd. "I was literally struggling, trying to survive and stay in school. SSTRIDE was that one-on-one place where I was nurtured."

Asked later about Ashby's comments, Anderson said the Miami native was a good student but needed guidance on how to transition to college and become a well-rounded student. He became a shining example of what students can accomplish through the program.

Ashby earned his medical degree at Cornell University and completed his internal medicine residency at Columbia University Medical Center, where he was later faculty. He completed a fellowship in cardiology at George Washington University and was named chief fellow, earned a master’s degree in public policy from Princeton University and trained in vascular medicine at Johns Hopkins University.

In addition to his many professional accolades, Ashby is the founder of Comprehensive Vascular Care in Miami and is clerkship faculty at the Fort Pierce Regional Campus. He is also part of the Erase the Hate organization, which works with youth in Miami’s Overtown and Liberty City areas to create art and music and reduce gun violence. He works with the Miami Rescue Mission Clinic, providing free care to the homeless, and he has established an internship program to help youth wanting health-care careers.

If Anderson "had gotten paid for all the work she did, she'd be swimming in Scrooge McDuck money," Ashby said with a chuckle. Looking directly at her, he concluded by saying, "I appreciate you. I honor you. I wouldn't be here without you."

Kandis Adkins, M.D., had planned to pursue a pharmacy degree after completing her undergraduate degree at Florida A&M. She changed her career path after tutoring USSTRIDE members in chemistry, physics and calculus and bonding with pre-med students in MAPS.

Adkins completed medical school and a residency in anesthesiology at Indiana University, followed by a fellowship in critical care at Duke University.

Now an associate professor at the University of Louisville School of Medicine in intensive care anesthesiology and current president of the Falls City Medical Society, Adkins is very involved in her community and improving access to health care. In addition, improving that access with more diversity among providers can lead to better outcomes.

"Research shows that racial concordance improves communication, trust and outcomes because patients are more likely to follow the provider's advice," she said.

Adkins also believes in “paying it forward.”

“It is important that all of us who were given a hand-up to get where we are remember to reach back and help those who come after us,” she said.

Adkins, Ashby, and the Sullivans were among many participating SSTRIDE alumni and College of Medicine faculty who funded scholarships so pre-med and medical students could attend the conference.

Paying dividends, and looking forward

Anderson continues to inspire her former students. This year, she completed her doctorate in education at St. Edward's University with an emphasis in higher education and leadership change.

She gave the keynote address at Saturday’s banquet, sharing her doctoral dissertation research: a study quantifying the success of the SSTRIDE strategy while adding a qualitative aspect that lent “heart” to the success stories. Her research also gave a name to the approach SSTRIDE has evolved into over the past 30 years -- Community of Practice -- a real-world authentic learning environment where like-minded students work together through engagement, knowledge-sharing and social connection to share, collaborate, inspire, and intellectually stimulate one another.

Yet, there is more to do. Black men continue to be the most underrepresented demographic in American medicine. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) reported earlier this year that only 5.7% of physicians in the United States are Black, and less than 3% are Black men. AAMC and the National Medical Association are working on a joint collaborative to increase the number of Black men in medicine, using the kind of early intervention techniques that SSTRIDE pioneered.

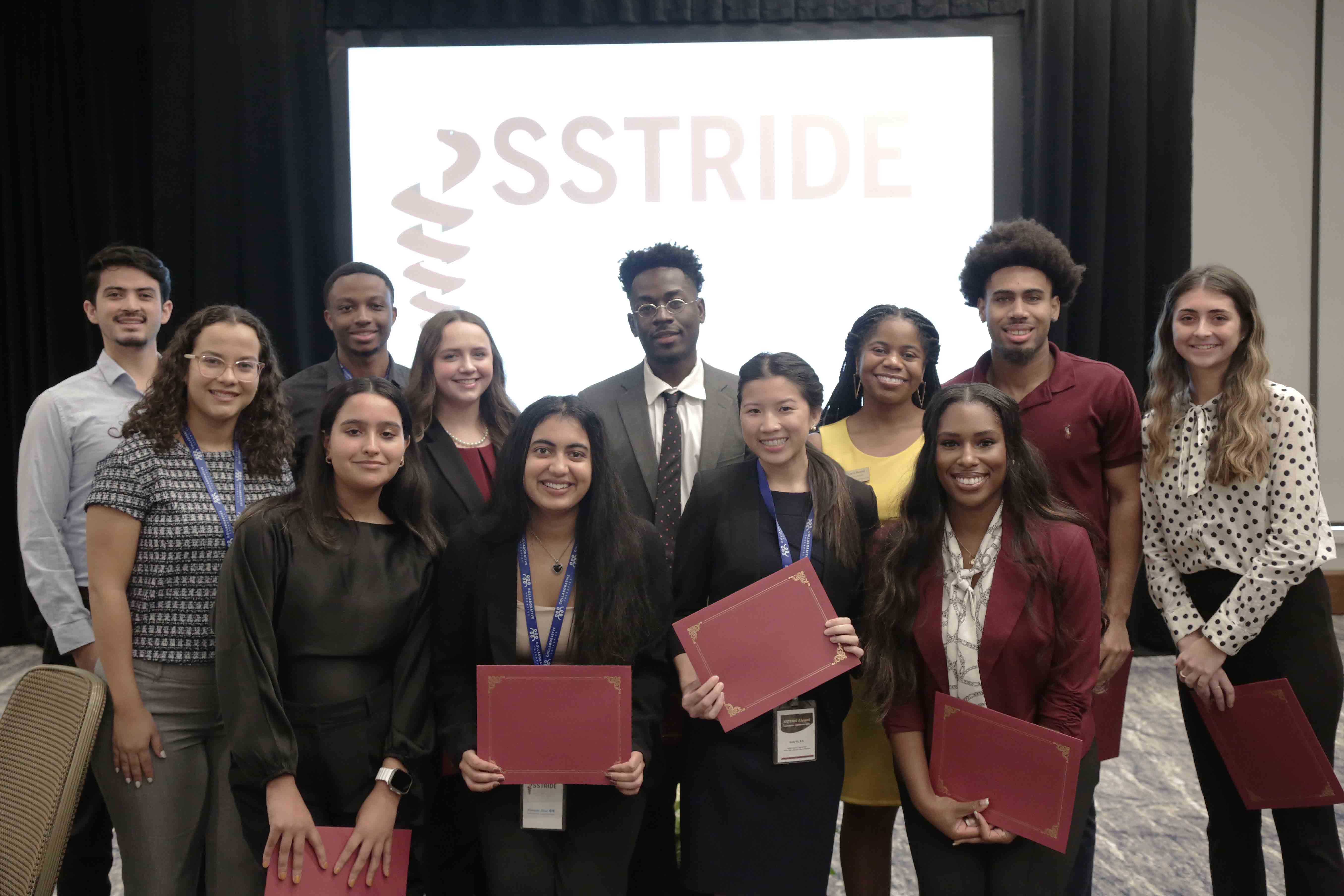

And there is encouraging news: Half a dozen SSTRIDE members scored above the 90th percentile on the MCAT this cycle after being tutored and immersed in USSTRIDE"s Community of Practice. One student, Florida State senior Elijah Doriscar, scored in the 98th percentile on his first attempt. Doriscar also placed first in the student research fair held as part of the weekend’s activities, which included poster presentations by SSTRIDE, IMS undergraduate and college medical students. Sonya Ottich, a junior, placed second and second-year medical student Kendall placed third.

In her closing remarks, Dr. Thesla Berne-Anderson asked those in attendance to join her in support of the SSTRIDE Legacy Initiative, a medical, health-care and STEM professional network with a next-level goal of attracting more minority, poor and rural students to careers in medicine.

"I am not a physician, but I am Dr. Anderson, and I wouldn’t change a thing," she said. "My purpose was to be involved in the making of doctors."

Choking back tears, she also offered a heartfelt appreciation:

“Even though I have helped you, you have helped me even more, and I thank you!”

Contact Audrey Post at audrey.post@med.fsu.edu

Photo Captions:

Spotlight Photo on Home page: Thesla Berne-Anderson, Ed.D., SSTRIDE founder and now executive director of pre-college and college outreach programs, addresses attendees at the SSTRIDE Leadership Development Conference held Dec. 1-3, 2023, in Orlando.

Photo at top right: Thesla Berne-Anderson shows off her nameplate presented by Anthony Speights, M.D., which includes her doctorate credential. Speights also presented an award honoring her 30 years of service to the FSU College of Medicine.

Photo of couple: Rashad Sullivan, M.D., and his wife, Natalie Alphonse Sullivan, M.D., approach the podium as hosts of the SSTRIDE 30th anniversary banquet.

Photo of panel discussion: Brittany Foulkes Crenshaw, M.D. (internal medicine), far left, and Bernard Ashby, M.D. (vascular cardiology), second from left, facilitate a panel discussion about the lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Panelists were, continuing from left, Haria Henry, M.D. (family medicine and Global Health Fellow); Joshua Golden, DDS, MPH; Inaki Bent, D.O., MBA (primary care/internal medicine), and Kalonji Cole, M.D. (senior internal medicine resident.) Crenshaw earned her M.D. at the FSU College of Medicine. The others earned their undergraduate degrees at FSU and participated in one or more of the College of Medicine's outreach programs: SSTRIDE, USSTRIDE, MAPS and the Bridge to Clinical Medicine.

Photo of student research presenters: Twelve Florida State University and Florida A&M University students presented their research at the SSTRIDE Leadership Development Conference. Row 1, from left: Nicole Bishop, Elora Mukhopadhyay, Holly Vu, Alexis Kendall (3rd place). Row 2: Michelle Martinez, Madeline McKenzie, Bertin Cenatus, Kiana Reaves, Kelton Williams, Sonya Ottich (2nd place). Row 3: Andres Felipe Gil Arana, Elijah Doriscar (1st place).

(Photos by Mark Bauer, College of Medicine director of creative services)